Big factors in each NH town's COVID vaccination success: outreach, demographics

The New Hampshire towns that have reached vaccination rates of 70% and higher – and there are fewer than 10 – have this in common: They leveraged personal relationships and viewed no outreach as too small.

When the local church let Jackson’s emergency management director, Emily Benson, know an older couple was struggling to navigate the vaccine registration site, she walked them through it via a Zoom screen share. The Lancaster Fire Department runs a vaccine out to any homebound residents who call. The Public Health Council of the Upper Valley extended personal invitations to vaccination sites, one phone call at a time.

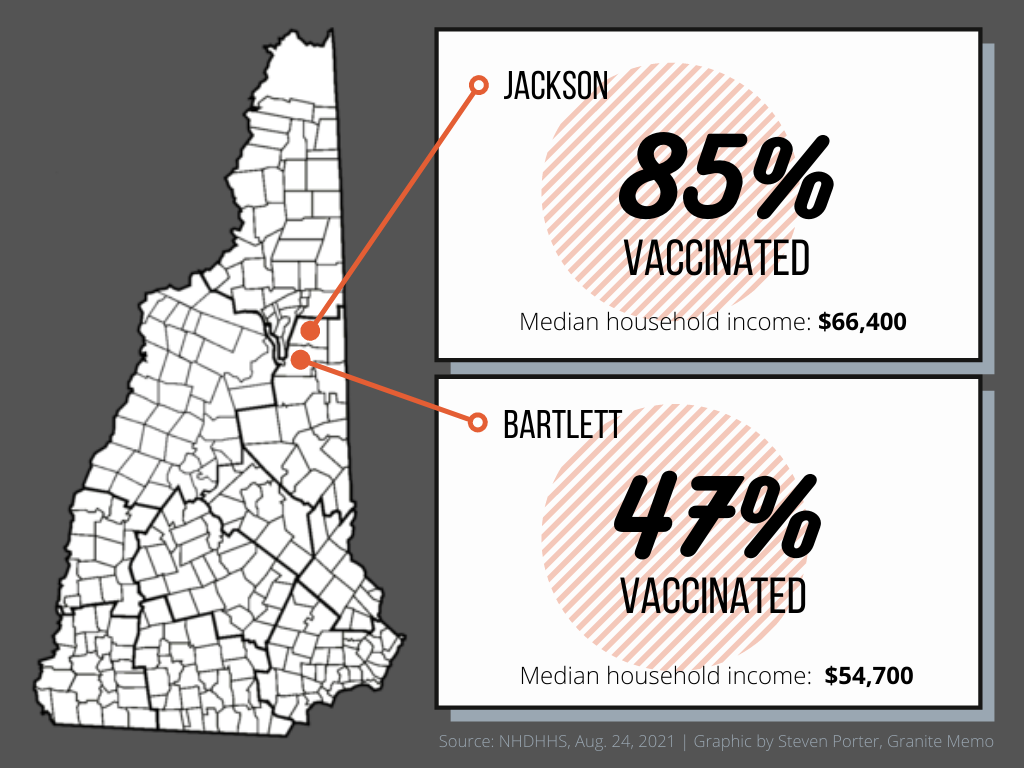

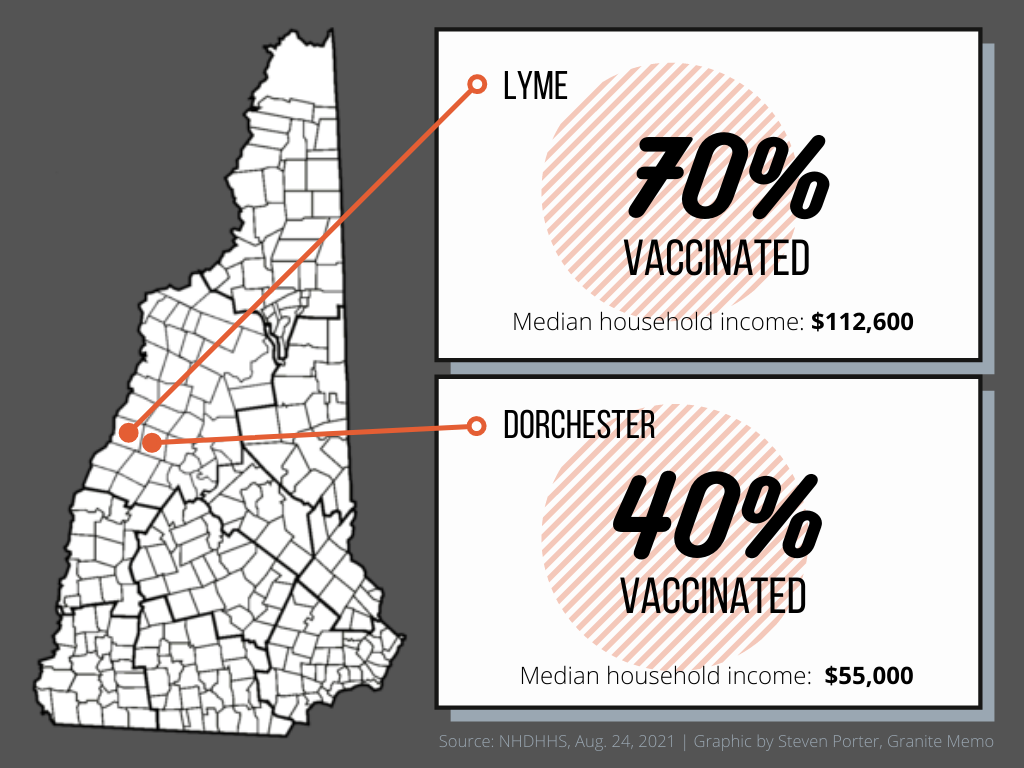

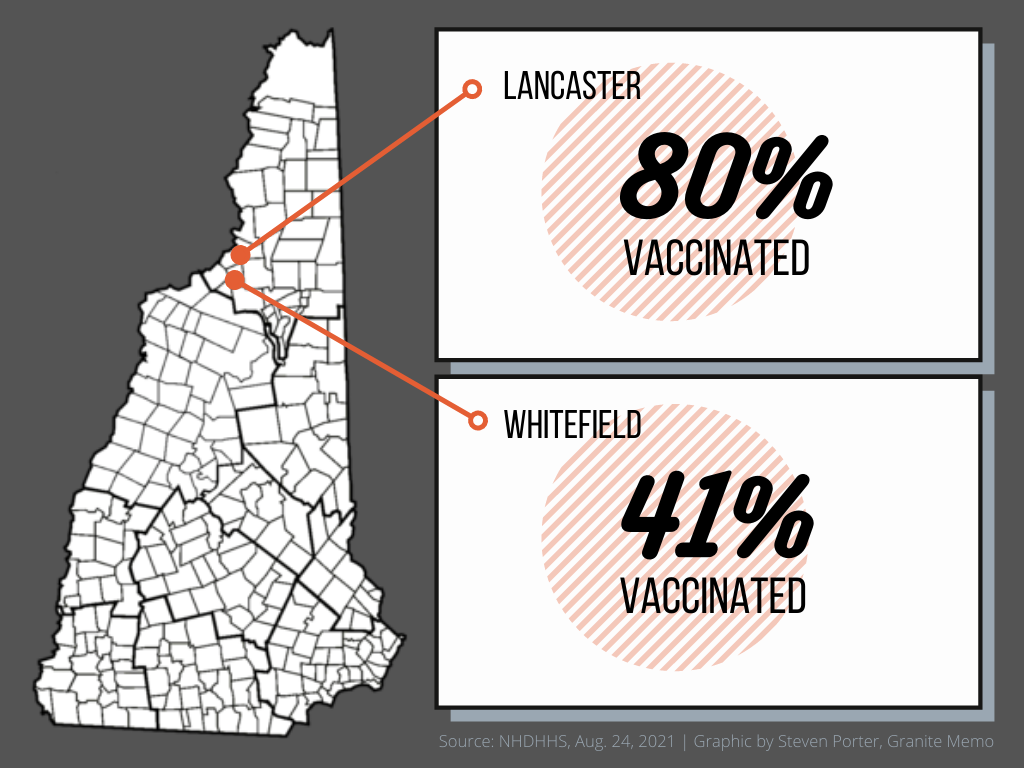

It’s been a winning strategy. While the state’s fully vaccinated rate has hovered around 54% of all residents and 61% of eligible residents for weeks, Jackson has fully vaccinated about 85% of its full population, Lancaster about 80%, and Lyme, in the Upper Valley, nearly 70%, according to the state’s COVID-19 dashboard.

Those numbers become even more significant when compared with the vaccination rates of their neighbors. Dorchester, next to Lyme, is at 39.6%; Whitefield, adjacent to Lancaster, has reached 40.9%; and Bartlett, a neighbor to Jackson, is at 47%.

It raises an obvious question: Why such different rates?

Outreach is a big part of the answer, but demographics matter, too.

Jackson and Bartlett

Bartlett’s health director, Vicki Garland, made no less of an effort to get residents vaccinated. She once asked four strangers outside a local store if they wanted a vaccine when she learned the local school site had four extra doses.

"There is a very different socio-economic make-up between (Jackson and Bartlett)," she said. (Bartlett’s annual median household income is $54,700; Jackson’s is $66,400.)

"We have people working two or three jobs to make ends meet. We have a higher percentage of free or reduced lunch," Garland said. "When people work multiple jobs to keep food on the table, it’s not always easy to get the vaccine. And they think, 'If there are side effects, am I going to miss work because I can’t afford to miss work?'"

Studies have shown vaccination rates are higher among people over age 50 and among those with higher education levels. Income plays a role too with unvaccinated rates a bit higher among those living in households earning less than $50,000 a year. That was borne out in an April University of New Hampshire Survey Center poll, where 84% of respondents who had done post-graduate work said they were partially or fully vaccinated, compared to only 55% of respondents with a high school diploma. The survey found the unvaccinated also tend to be Republican or Republican-leaning, and people who identify as non-white.

Lyme and Dorchester

Alice Ely, executive director of the Public Health Council of the Upper Valley, said Lyme and Dorchester illustrate the divide. The towns have drastically different median household incomes ($112,600 in Lyme versus $55,000 in Dorchester) and educational attainment (66% of Lyme residents hold a bachelor’s degree or higher while only 26% do in Dorchester).

“(Lyme) is a different kind of community in terms of how people connect with one another,” Ely said. “(In Lyme), they value being in the community with each other. Dorchester is more spread out, and I don’t think it’s unfair to say it’s a community where people value their privacy. They came together in some way, but for the most part, they want to be left alone.”

Case counts may also matter, Ely said: Lyme has reported 27 cases among its 1,675 residents, while Dorchester, population 356, had reported eight as of Monday. “Why would they rush out if the cases have been so low?”

As the state adjusts its vaccine outreach with an additional mobile vaccine van and new advertising campaign aimed at younger residents, even public health and emergency management officials in towns with high vaccination rates say they are also keeping at it.

New Hampshire and Vermont

Vermont, which leads the nation in vaccination rate with 75% of eligible residents fully vaccinated and 85% with at least one dose, may be a source of inspiration. Dr. Mark Levine, Vermont’s health commissioner, called the state’s vaccination campaign relentless.

“I think it’s being patient because it goes slower,” he said. “We are nibbling away at it. The goal for us here is meeting people where they are.”

Ely said the outreach in her area was done with the same sensitivity in mind. That included offering clinics on Fridays for those worried about side effects keeping them from work for two days.

“There are some who are making (opposition to a vaccine) a matter of principle and some who have very real concerns,” Ely said. “It doesn’t do any good to be angry at them. It’s much better to listen and try to understand.”

There’s plenty of opportunity for increasing New Hampshire’s numbers, with nearly 545,000 people still not vaccinated. (The state dashboard does not say how many of those are old enough to be eligible, however.) The announcement that the Food and Drug Administration has given the Pfizer vaccine full approval may persuade some. But outreach – with the right approach – remains crucial.

Highly localized outreach efforts make progress

Weeks Medical Center in Lancaster, which ran weekend clinics until June, even when it was so cold volunteers had icicles on their eyebrows, is expanding its community clinic again to offer more appointments to those who’ve hesitated to be vaccinated.

Jennifer Bach-Guss, chief nursing officer, said hospital leadership is also planning a community forum for residents to ask a clinician questions about the vaccine, either by Zoom or in a large conference room with space for social-distancing. Local medical offices will also offer vaccines to patients who come in for routine medical appointments, she said.

“The hope is that the best way to get someone vaccinated is to have someone they know or care about get vaccinated and have them see nothing bad happens,” Bach-Guss said.

Throughout the pandemic the North Country Healthcare system staff met weekly, and often daily, with community leaders from area schools, towns, hospitals, and primary care offices to get a broad understanding of gaps in services. Transforming a shuttered elementary school in Berlin into a vaccination site proved to be a welcoming place for educators and families. And the hospital emergency room in Berlin is now offering vaccinations to patients, said James Patry, chief of marketing for North Country Healthcare.

Hooksett reached its 75.6% vaccination rate by also making vaccines easy to get, said Emergency Management Director Steven Colburn, who is also the fire chief. Southern New Hampshire University hosted a state vaccination site six days a week and kept it open 12 hours a day.

“I don’t think we did anything super special,” Colburn said. “We did a lot of PR through social media, but I think, honestly, a lot of it was that it was just convenient.”

A similarly diverse team met weekly in Lyme until June and held a Zoom panel discussion to answer residents’ COVID-19 questions. Judy Russell, director of the Converse Free Library in Lyme, gave the library’s homepage over to pandemic resources and information.

“The one message that we wanted to get out was that there are people available at any time to answer any questions you have to get the facts you need to make decisions,” Russell said. “To keep the line of communication open to be there so when they were ready to get the vaccine, they knew where to go.”

Benson, of Jackson, also took advantage of local connections she’d made through years of teaching in town and her public health work in the area. So did town officials and area social service agencies. The church and senior center knew who was vulnerable among their groups. The town’s newsletter carried regular COVID-19 and vaccination updates. Community groups that deliver holiday food and gift baskets to neighbors in need looked at their lists, too.

Those relationships, easier to forge in a small town with 860 people, were critical, Benson said: “If you don’t have trust, as we have definitely seen, it doesn’t matter what you do.” She acknowledged another advantage, too: demographics.

“We are a very highly educated town with fairly high property values,” she said. “It’s really a reflection of the residents themselves. They respect and look at the facts and proceed accordingly with their health care. It’s an understanding that it’s not just about my health but the health of our community.” ∎